|

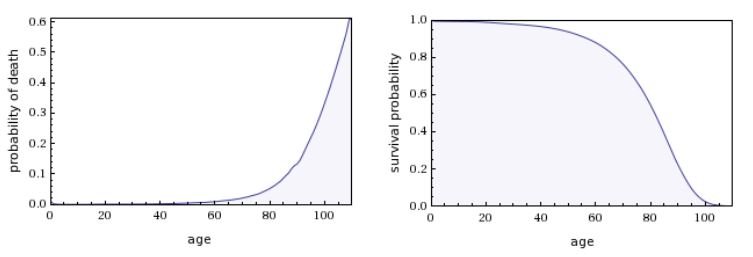

My father turned 87 at the end of last week. He is still in very good shape, is physically active and retains all of his mental faculties. We had a nice conversation on his birthday and I asked him what it was like to have survived for so long when most of his contemporaries are no longer with us. He recounted a story of a recent trip he had taken with my brother. My brother was attending a professional conference at a nearby resort and my father went with him to keep him company for a few days. He said he was surprised at how favorably he was received. They met another attendee who had brought his children, aged about 7 and 9. After meeting him one day, they treated him like he was a cherished grandparent the rest of the time they were there, hugging him and talking with him excitedly whenever they saw him. I said to him, “Don’t you know that people like you are relatively rare?” Most men do not survive to your age and the ones that do are usually not able to live ordinary lives due to physical or mental infirmity. To see such a person outside of retirement communities is like spotting a rare bird outside of captivity. He said he had never thought about it that way, but that it seemed to be true. Let’s consider what getting really old in U.S. society looks like through the Lenses of Wisdom. The obvious lens to look through first is the Fractal Lens. Looking through it, we see the math that made the life insurance industry possible – the Gompertz Law of human mortality, which was first derived by British actuary Benjamin Gompertz in 1825. The Gompertz Law of human mortality states that your chances of dying tend to double about every eight years. In other words, human mortality in the aggregate is governed by a mathematical exponential function, as the Fractal Lens tells us is the fundamental math behind most of the important things in life. Since our chances of dying in the next year are very small when we are young, the death rate of our cohort remains small through the first decades of life. However, once it begins to rise in our later years, it takes off like a rocket. When we are 60, our chances of dying in the coming year are less than 1%. When we are 70, they move up to about 2%. But by the time we reach 80 years of age, our chances of dying in the next year are 5%; at 85, 8.5% and at 90, over 14%. These charts show how quickly mortality increases after age 70 and even more dramatically after age 80. Life becomes a slippery slope. And although these curves have shifted to the right as overall life expectancy has increased in the past 100 years, the shapes of the curves have not changed from what Gompertz observed in 1825. The effect is even more pronounced for men, because they live shorter lives on average than women. For men in the United States, the chances of dying in the coming year at age 60 are over 1%; at age 70, 2.3%; at age 80, 6%; at age 85, 10%; and at age 90, 16.6%. In terms of percentages as to how many have survived in a given cohort, at age 60, 86% will still be alive; at age 70, still approximately 74%. However, by the time a group of men reaches age 80, the survival rate is down to only 51%. At age 85, only 35% survive and at age 90, only 18%. By contrast, women do not sink below the 50% survival rate until age 85. For my father at age 87, he has already outlived almost 70% of the other men born in 1929. Twelve percent of these surviving men will die in the next year and one-third will be gone in the next three. In raw numeric terms, there are approximately 6 million people over the age of 85 in the United States, or about 2% of the population. Only about one-third are men, or 2 million. By the time people reach that age, one-third of them are stricken with Alzheimer's disease, and assuming a few other disabilities, it is fair to say only about 1 million men or less over the age of 85 in the United States are capable of normal living. This is about 1/300 (0.0033) or a third of a percent of the population. It would appear that the magic really begins for a man around age 85. By that time a man will have outlived two thirds of his contemporaries, and is becoming rare. My father has become a rare bird indeed and is becoming exponentially more rare; each day, approximately 10 of his contemporaries no longer arise. The statistics also match the family history. Out of the seven male siblings in his and my mother's families, only two, or 28% remain, and the other lives in a retirement facility and suffers from dementia. By contrast, all six female siblings are alive and none live in institutions. I told him that he is becoming more magical every day and he ought to think about that every morning when he gets up. Looking through the Mimetic Lens, we can next consider how aging in our Western society differs from traditional, more hierarchical ones. In Atul Gawande's recent book, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, he describes the latter part of the life of his grandfather in rural India: "MY FATHER’S FATHER had the kind of traditional old age that, from a Western perspective, seems idyllic. Sitaram Gawande was a farmer in a village called Uti, some three hundred miles inland from Mumbai, where our ancestors had cultivated land for centuries. . . . he was more than a hundred years old. He was, by far, the oldest person I’d ever known. He walked with a cane, stooped like a bent stalk of wheat. He was so hard of hearing that people had to shout in his ear through a rubber tube. He was weak and sometimes needed help getting up from sitting. But he was a dignified man, with a tightly wrapped white turban, a pressed, brown argyle cardigan, and a pair of old-fashioned, thick-lensed, Malcolm X– style spectacles. He was surrounded and supported by family at all times, and he was revered— not in spite of his age but because of it. He was consulted on all important matters— marriages, land disputes, business decisions— and occupied a place of high honor in the family. When we ate, we served him first. When young people came into his home, they bowed and touched his feet in supplication. In America, he would almost certainly have been placed in a nursing home. Health professionals have a formal classification system for the level of function a person has. If you cannot, without assistance, use the toilet, eat, dress, bathe, groom, get out of bed, get out of a chair, and walk— the eight “Activities of Daily Living”— then you lack the capacity for basic physical independence. If you cannot shop for yourself, prepare your own food, maintain your housekeeping, do your laundry, manage your medications, make phone calls, travel on your own, and handle your finances— the eight “Independent Activities of Daily Living”— then you lack the capacity to live safely on your own. . . My grandfather could perform only some of the basic measures of independence, and few of the more complex ones. But in India, this was not of any dire consequence. His situation prompted no family crisis meeting, no anguished debates over what to do with him. It was clear that the family would ensure my grandfather could continue to live as he desired. One of my uncles and his family lived with him, and with a small herd of children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews nearby, he never lacked for help. The arrangement allowed him to maintain a way of life that few elderly people in modern societies can count on. The family made it possible, for instance, for him to continue to own and manage his farm . . . . . . Throughout his life, he awoke before sunrise and did not go to bed until he’d done a nighttime inspection of every acre of his fields by horse. Even when he was a hundred he would insist on doing this. My uncles were worried he’d fall— he was weak and unsteady— but they knew it was important to him. So they got him a smaller horse and made sure that someone always accompanied him. He made the rounds of his fields right up to the year he died . . . My grandfather finally died at the age of almost a hundred and ten. It happened after he hit his head falling off a bus. He was going to the courthouse in a nearby town on business, which itself seems crazy, but it was a priority to him. The bus began to move while he was getting off and, although he was accompanied by family, he fell. Most probably, he developed a subdural hematoma— bleeding inside his skull. My uncle got him home, and over the next couple of days he faded away. He got to live the way he wished and with his family around him right to the end." The view of Gawande of his grandfather may not have been so idyllic from the point of view of the family members who physically cared for the man. Such care can be a struggle, even with many hands to help. But in an archaic society like that of rural India, to fail to care for one's elders in the home is taboo. The description is also overly romantic, because the grandfather does not actually receive special treatment for anything he has done on merit, but simply for the place he occupies in that society. His experience as an old woman, for example, would be vastly different, no matter how accomplished she might be. For someone who encounters an old man in that society, he recognizes the elder as a reflection or mimetic representation of the entire society. By contrast, life for the elderly in Western society is not mainstream and is relatively segregated. The elderly and the rest of society do not mix very much, because the word "retirement" generally connotes that the person ceases to hold a position of importance or high value. To be considered important in Western society, one must typically be working in a high-profile career, be famous, be extremely wealthy, or some combination of the three. Otherwise, one's importance is largely limited to family and particularized community. So how does a younger person in a Western society relate to an older one in mimetic terms? Recall that in the Western thought process as developed from Christianity, all are considered to have equal value at some level. So as older person is not recognized so much as a mimetic reflection of society, but as a mimetic reflection of self. Thus, when a younger person in a Western society encounters an older one, the thought process is not "this is what makes our society ordered and work properly", but "this could be me." This creates a dichotomy between how we treat healthy older people and unhealthy ones, and explains the vast differences. The infirm, the disabled and those near death are generally avoided and usually segregated into nursing homes and hospitals. Even family members often struggle with avoidance issues. This is in large part because no one wants to think of themselves in such states. On the other hand, the healthy elderly are a cause for celebration. One of the ways of achieving a modicum of fame is simply to live long enough and be healthy enough. The relative scarcity and novelty of such people is enough to make them popular. For example, a 106-year old woman named Virginia McLaurin was recently invited to the White House to meet the President of the United States and the First Lady. It probably would not have been much of a story, but for the fact that she was lucid, walking and even dancing -- everything that one would hope to be at that age if one makes it that far. Here she is in action: This is an example of the positive side of mimetics -- celebrating what which wish to become, as opposed to competing with a rival for an object of desire. We instinctively feel a magic that surrounds such people, and hope that we can acquire some of it for ourselves. There is a natural desire to physically touch such people, hoping the some of the magic might rub off. Looking through the Prospecting Lens, our strongest reactions to the healthy elderly clearly fall within System 1 heuristics. The relevant heuristics include: COHERENT STORIES (ASSOCIATIVE COHERENCE). To make sense of the world we tell ourselves stories about what’s going on. We make associations between events, circumstances, and regular occurrences. The more these events fit into our stories the more normal they seem. Things that don’t occur as expected take us by surprise. To fit those surprises into our world we tell ourselves new stories to make them fit. We say, “Everything happens for a purpose,” “God did it,” “That person acted out of character,” or “That was so weird it can’t be random chance.” Abnormalities, anomalies, and incongruities in daily living beg for coherent explanations. In the case of the healthy elderly, we tell ourselves that they must "have lived good lives" or done something special to have survived so long and in such good shape. We do not want to think that there may of been some elements of luck involved. CONFIRMATION BIAS and OVERLOOKING LUCK. These are the tendencies to search for and find confirming evidence for a belief while overlooking counter examples. “Jumping to conclusions is efficient if the conclusions are likely to be correct and the costs of an occasional mistake acceptable, and if the jump saves much time and effort. Jumping to conclusions is risky when the situation is unfamiliar, the stakes are high, and there is no time to collect more information." In the case of the healthy elderly, if they are like us in some way or in some habit, we often attribute the likeness or habit to their condition as one of their "secrets" to a healthy long life. We want to be able to tell ourselves that we are "doing the right thing" in what we are eating or perhaps our religious preferences, or at least "not doing the wrong thing" in the cases where we learn that the person habitually smoked or drank. Going along with Confirmation Bias in tandem is THE LAW OF SMALL NUMBERS. Our brains have a difficult time with statistics. Small samples are more prone to extreme outcomes than large samples, but we tend to lend the outcomes of small samples more credence than statistics warrant. System 1 is impressed with the outcome of small samples but shouldn’t be. Small samples are not representative of large samples. In the case of the healthy elderly, we often erroneously attribute meaning to the fact that this particular person survived intact, when the reality is that most people will not, regardless of how they live their lives. THE HALO EFFECT. “This is the tendency to like or dislike everything about a person—including things you have not observed." The warm emotion we feel toward a person, place, or thing predisposes us to like everything about that person, place, or thing. Good first impressions tend to positively color later negative impressions and conversely, negative first impressions can negatively color later positive impressions. This is perhaps the most predominant System 1 effect. There is a strong tendency in Western societies to immediately like healthy elderly people and, conversely, to immediately want to mentally distance oneself from an elderly person who is infirm. Under a rational System 2 analysis, there is little or no downside to following our System 1 instincts in cherishing our healthy elderly. It brings joy into our lives. System 2 actually helps us more with the infirm -- to see them as victims to be comforted and not symbols of mortality to be avoided -- and to come to terms with the reality that all of us will die someday, and might become infirm before we do. It is easy in Western societies for the elderly to become discouraged, regardless of their health. Older men, in particular, often do not survive more than one year following the death of a spouse unless they remarry. It does us all some good to stop and remind them of how magical they really are now and again. And that they are becoming more magical every day just by getting up and going about the ordinary business of living their lives and interacting with others. * * * * * * * So how does one become magical? Well, first by being a bit lucky. No one can control one's genetics or the vagaries of diseases or accidents. But supposing that one is lucky enough to live that long, relative health becomes the critical factor. While we are better in some ways about caring for ourselves than we were a generation ago, especially as regards to smoking, the so-called "epidemic of obesity" is likely to exclude many from a magical old age if not addressed earlier in life. Frequently using whatever one has in terms of physical or mental capacity has also been show to increase the likelihood that one will keep some of it. Finding meaning in one's life and especially one's relationships is also a means to preserving health and warding off depression and potential reliance on unhealthy substances. But that's the technical answer. I think I might prefer this poetic one, especially as applied to relationships, as I have adapted from Margey Williams The Velveteen Rabbit: "What is MAGICAL?" the Velveteen Rabbit asked the Skin Horse one day. "Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?" "Magical isn't how you are made," said the Skin Horse. "It's a thing that happens to you. When someone loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Magical." "Does it hurt?" asked the Velveteen Rabbit . "Sometimes," said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. "When you are Magical you don't mind being hurt." "It doesn't happen all at once," said the Skin Horse. "You become. It takes a long time. That's why it doesn't happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Magical, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in your joints and very shabby. But these things don't matter at all, because once you are Magical you can't be ugly, except to people who don't understand. But once you are Magical you can't become ordinary again. It lasts for always." Now that's the Country of Old Men that I aspire to live in some day.

4 Comments

|

I have always been curious about the way the world works and the most elegant ideas for describing and explaining it. I think I have found three of them. I was very fond of James Burke's Connections series that explored interesting intersections between ideas, and hope to create some of that magic here. Archives

February 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed